Intelligent Life Magazine, March/April 2015

- DPP in the Media

- 11 Feb 2015

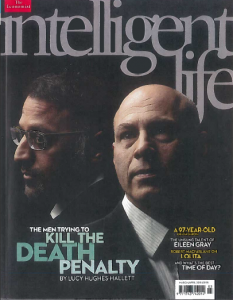

Capital punishment is slowly dying out, one country at a time—largely thanks to two British lawyers. How do they do it? Lucy Hughes-Hallett joins them in Belize

From INTELLIGENT LIFE magazine, March/April 2015

UGANDA, 2005. TWO London-based lawyers, Parvais Jabbar and Saul Lehrfreund, are members of a group visiting a heavily fortified prison outside Kampala. They are led through an archway into a yard crammed with men. There are nearly 400 of them, all standing or squatting in the blazing sun, all in white shirts and shorts. And all condemned to death.

They have convictions for murder, which carry a mandatory death sentence: no mitigating circumstances can be taken into account. Some of the men are still in their teens. Others have been living with the prospect of being executed for 20 years or more. When they were ordered out of their cells this morning, many assumed that they were being taken out to be hanged. Instead they find themselves face to face with people doing their utmost to prevent that day ever coming. As the visitors appear, the convicts rise up, and clap, and begin to sing. A decade later, Lehrfreund will say, “We all left the prison speechless, all moved pretty much to tears.”

LEHRFREUND AND JABBAR are the executive directors of the Death Penalty Project (DPP), a charity that provides free legal representation to those condemned to death. Personally, both would like to see capital punishment abolished everywhere, but they don’t march in the streets waving banners. They don’t harangue politicians. They don’t barge in where they’re not wanted. They use the law to change the law.

To those who invite them to help with a case, they offer legal advice based on long experience. They instruct leading British barristers, who work for the DPP unpaid. They fly to India, Singapore, Africa, the Caribbean. They form relationships with judges and politicians, lawyers and NGOs. They commission reports exploding myths about the death penalty: that it is an effective deterrent; that for a politician to advocate its abolition is electoral suicide. They organise conferences and workshops from Trinidad to Taiwan, showing local lawyers what can be done in defence of those condemned to death. They operate like Shakespeare’s Portia, who didn’t protest at the barbarity of cutting a pound of flesh from the Merchant of Venice’s side, but raised so many caveats (no blood must flow, the flesh must weigh precisely one pound—no more, no less) that she made the unspeakable impossible. So the DPP achieves its ends by raising meticulous objections, imposing reasonable restrictions, always working within the rules, however frustrating those rules may be.

The consequences of the two lawyers’ toil have been momentous, not only for the hundreds of criminals they’ve saved from execution, but for countless future offenders. The British legal system, and its emulators, are based on precedent. Every time a death-sentence is commuted or quashed, it becomes less likely that subsequent death sentences can be made to stick. Every time a piece of law is overturned in one country, it ceases to be tenable in others. And this even holds true across continents. In 2002 the DPP brought cases in appeals from three Caribbean countries which resulted in a ruling that a mandatory death sentence was unconstitutional. Judges must be able to take mitigating factors into consideration; even killers should have the right to make a case for a fate better than death. Three years later, half a world away in Uganda, in response to a case brought by a local law firm with the DPP’s assistance, and invoking the precedent set in the Caribbean, the supreme court agreed that the mandatory death penalty was unconstitutional in Uganda too.

All 417 men in that hot prison compound, singing to Jabbar and Lehrfreund, to Sir Keir Starmer QC (the barrister acting for them, later Britain’s director of public prosecutions) and to their Ugandan colleagues, were celebrating the return of hope. In Uganda alone, 160 death sentences have since been commuted or struck down. As Lady [Vivien] Stern, the former head of Penal Reform International, says, “It’s an amazing phenomenon. Two guys having such a huge effect.”

THE STORY BEGINS in 1975, when Dennis Muirhead, of the law firm now called Simons Muirhead & Burton, took on the case of Michael de Freitas, aka Michael X, who had been convicted of murder in Trinidad. Muirhead handled his appeal to the Privy Council in London. It was thrown out, and de Freitas was executed. But it was the beginning of a process that was to save many other lives. “That case spawned a lot of publicity,” says Anthony Burton, now the senior partner. De Freitas was well known in London’s cultural and counter-cultural circles, and Muirhead had friends and clients in the music business. V.S. Naipaul wrote a story about the murder. John Lennon donated his famous white piano towards de Freitas’s legal costs. “Actually there weren’t any costs,” Lehrfreund says, “the lawyers were working pro bono,” but the gesture was still useful, generating press coverage. “The word got to Jamaica, and the floodgates opened,” Burton says. “We got letter after letter from people on death row there.”

Most of those cases were handled by another partner in the firm, Bernard Simons, and a few trainees. “We were a very small firm,” Burton says. “We couldn’t say no to these cases, but soon we were drowning in them.” Most of the appeals were dismissed, most of the clients executed. Finally, in 1992, Lehrfreund was recruited, fresh out of university, working three days a week for not much money, to take charge of a new department of the firm, named the Death Penalty Project. Simons died six months later. “From that day in May 1993,” says Lehrfreund, “there was just a very young, inexperienced, pretty hopeless lawyer handling these cases with very high stakes, not knowing what I was doing at all.”

Young and inexperienced maybe, but far from hopeless. In 1994, with Lehrfreund on board, the firm took on the case of two convicts in Jamaica who’d been awaiting execution for 14 years and had been told three times that they were about to be hanged. The case of Pratt and Morgan proved historic. Nine barristers appeared before the Privy Council. “Loads of Jamaican lawyers came over,” Jabbar says. They won a ruling that no one who had been on death row for more than five years should be executed. Hundreds of prisoners across the Caribbean had their sentences commuted. “From that day on,” Lehrfreund says, “we became internationally known.”

In 1995 Parvais Jabbar joined Lehrfreund, working for no pay at all for the first year. Two men in their 20s, with no budget and half a secretary, working out of a tiny room, constituted the only hope, as Lehrfreund says, for anyone convicted of murder in 13 countries with high murder rates. “In Jamaica alone there were hundreds of people on death row: 75% lost their appeals. There was only one place to come. They came to us. We had huge amounts of work.”

Twenty years on, the DPP, though still in Simons Muirhead & Burton’s offices, is an independent charity. Its directors have been awarded MBEs. They have a back-up team of two now, and the respect of the legal world, but they’re still just two people, working flat-out. And their proudest boast, in Lehrfreund’s words, is this. “In 20-plus years, we’ve had some close shaves, but no one has been executed on our watch.”

BELIZE, NOVEMBER 2014: another prison, another song. The DPP team are given a tour by the prison governor, John Woods. A Texan and a fervent Christian, Woods had it written into his contract that he would never carry out an execution. “We may not be that keen on all the religious stuff there,” Jabbar says, “but he has really turned the place around.”

He shows us the prison radio station, which broadcasts uplifting thoughts all over the compound. We pass a scatter of concrete buildings, walls decorated with biblical scenes in chalky pastel colours. We see vultures on high wire fences and chickens scratching in weedy ground. In the barnlike youth facility, teenage prisoners eye us through barred openings.

On to the rehabilitation centre. A door opens and we’re walking up an aisle, flanked by about a hundred prisoners. Most are barefoot. Those who’ve been sentenced are in orange pyjamas. There are heavy gold chains around thick necks. Tall men with African features. Shorter Hispanic types. Faces with the dead-straight nose and wide cheekbones of the Maya. Behind us, painted on the wall in gothic script and candy colours, are the prayers and slogans of the 12-step programme. (“So are all those people addicts?” I ask Woods. “Everyone’s addicted to something,” he says. “It could be drugs. It could just be they need to change their lifestyles for the betterment.”) He introduces us, then everyone is on their feet singing. They begin with the Belizean national anthem and end with “If you’re happy and you know it, clap your hands.”

The prisoners, like schoolchildren, clap and stamp on cue. If they’re really that happy, I’ll eat my hat. But at least their situation is less desperate than it was when the DPP first took on cases in Belize. “It was the Wild West then,” says one of the barristers who have worked there. “There were dozens of people on death row.” Now there is only one.

“GIVE ME A lever long enough, and a fulcrum on which to place it,” Archimedes said, “and I shall move the world.” The DPP’s lever is the talent of the barristers Jabbar and Lehrfreund recruit to work for it unpaid. Their fulcrum, through a quirk of legal history, has been the Judicial Committee of the British Privy Council. As Bernard Simons realised in the de Freitas case, there are a number of countries—now independent, once British colonies—for whom the Privy Council in London is still the ultimate court. Commit a capital offence in the Bahamas or Jamaica, and your appeal, if you have a clued-up lawyer and can afford the costs (two big ifs), will eventually reach London. There—in a country where the death penalty was abolished half a century ago, where pleas of provocation, self-defence or mental incapacity are routinely accepted by judges—your conviction may, with the right representation, be overturned. A relic of colonialism, but a benign one.

Before we fly to Belize, I meet Lehrfreund and Jabbar in their Soho office to plan the trip. Also present are two barristers, James Guthrie and Edward Fitzgerald, who have worked for the DPP, unpaid, from the start. Guthrie is a Queen’s Counsel and recorder who has been head of his chambers. Fitzgerald, also a QC, was awarded a CBE in 2008 for services to human rights. Those services have included representing notorious figures from the Moors murderess Myra Hindley to Jon Venables, the child who killed another child, as well as acting for the Islamist cleric Abu Hamza. Such work can make a man unpopular, but it is in accord with the ethos of the DPP—and of British justice as a whole, which holds that everyone, whatever they have done, is entitled to a lawyer, and to fair treatment within the law.

The atmosphere is incongruously jolly. Fitzgerald is a big, talkative man with an all-over-the-place manner. His favourite word is “genial”, and it sums up his apparent persona. He doesn’t come to Belize this time, but I hear a lot of reminiscences there about Edward’s fondness for a now-defunct dive called the Club Amnesia, and of his wandering off—arms waving, linen suit crumpled, telling stories at top volume —into the no-go part of Belize City and returning hours later. But there’s more to Fitzgerald than Mr Geniality. He has been defending people on death row since before the DPP was set up, working with Bernard Simons on cases from Jamaica and Trinidad. “People were getting executed,” he says. “It was ‘Can you do something for this person?’ It was all hands to the pump.”

Jabbar and Lehrfreund pay tribute to his dedication and creative thinking. “For more than two decades”, they say, “he has led the legal movement to progressively restrict the imposition of the death penalty. Edward saves lives.”

Guthrie, suave and witty, is comparatively laid back. He has been appearing pro bono before the Privy Council for 20 years, and has acted in many of the DPP’s cases. He too has had gaudy nights in the Club Amnesia, but his favourite way of using down-time in Belize is to go fishing from the off-shore islands, wrestling with the bonefish that grow a metre long.

Behind Fitzgerald and Guthrie stand more barristers, including Julian Knowles QC and Keir Starmer QC, who acted in that historic case in Uganda. Behind them are many more volunteers, doctors and academics as well as lawyers. As Lehrfreund puts it, “There’s up to a hundred people who work on the Death Penalty Project.”

Why do these top-ranking silks take the DPP’s briefs, missing out on lucrative work, or precious free time? When I ask Fitzgerald about his motivation, he says, “Oh, it’s the foreign travel, the foreign travel!” and gives a great chortle. This is nonsense: in the time they spend in prison cells in hair-raising parts of the world, these people could be earning enough to pay for holidays in far more salubrious places. I ask again. “It’s a bit of a passion. I’m passionately against the death penalty.”

Guthrie’s answer is more measured. “It’s interesting work. I like the people. It’s not that I’ve got a great burning fire in my belly.” In fact, he believes that ardour would be out of place. “Lawyers are better off being objective.”

His Privy Council work isn’t all for the DPP. He has appeared on the other side, acting for governments. But for all his apparent cool, he’s been a trustee of the Death Penalty Project since its inception and gives it a lot of his time. His impartiality fits with his concern for fairness. “It’s important that the rights of people who are not able to command much general support get respected,” he says, “and that they are properly represented in court.” When Parvais Jabbar rang him early on Christmas morning, asking for much-needed advice on a difficult case in Belize, Guthrie dropped everything to work on it. “I apologised for bothering him and he said—classic James—‘It’s Christmas. It’s good to have something interesting to do.’ Most people don’t even pick up the phone at Christmas. But he pulled out all the stops.”

Fitzgerald and Guthrie are big beasts in the British legal world, and Jabbar handles them like a lion-tamer. While they tell stories of past exploits—a conviction for murder overturned, by dint of some all-night transatlantic phone calls, 20 minutes before the accused was due to be hanged; a quorum of high-court judges dragged from their beds in the middle of a bank-holiday weekend to quash a death sentence; a British high commissioner hastening down to a prison at dawn to threaten the governor with a murder charge if he went ahead with an illegal execution—Jabbar, smiling, keeps the agenda moving. In Belize I see him doing the same with dignitaries from the prison governor to the chief justice. He is polite but persistent with his questions. Including the big one: why, in Belize and elsewhere, does the death sentence still exist?

BELIZE NOVEMBER 2014. The team are going to present a report they have prepared, with the Bar Association of Belize, on vulnerable groups in the prison there —juveniles, the mentally ill, those held for inordinate lengths of time on remand. (Capital punishment is their primary focus, but once they have a connection with a place they will try to redress any breaches of human rights they see.) I’m going along to observe the way they work. “We don’t just walk into a place saying, ‘We’re here to save you’,” Jabbar tells me. “People contact us.”

This discretion is the secret of their success. As Vivien Stern says, “There are people working to abolish the death penalty who are messianic about it, awfully self-righteous.”

The DPP is expert at avoiding the kind of hostility such fervour can arouse. Since it became a registered charity in 2006, one of the chief funders has been the Oak Foundation. Its director, Adrian Arena, says: “There’s a difficult, even poisonous dynamic about British lawyers coming into these places, imposing their views.”

In Belize I see how careful Jabbar is to draw that poison, ensuring all the local authorities feel included, that no one’s back is gone behind. “It’s not easy,” says Arena. “But they’ve navigated that very, very carefully.”

Vivien Stern confirms this. “They don’t give the impression they’re thinking ‘you are backward people because you have the death penalty’. They’re just good lawyers saying, ‘whatever you do, the law should be respected.’”

In every country, they work alongside local lawyers. “It’s an important point that it’s not just a bunch of English guys going over and doing it all,” Edward Fitzgerald says. “There are a lot of Caribbean lawyers involved.”

Their initial invitation to Belize came from Simeon Sampson. A charismatic man with a wild laugh and energy untamped by time (he is 81), Sampson was a colonial civil servant before Belize got its independence. He changed course in his 60s to become a human-rights lawyer, fighting to get a fair deal for those on death row. “He’s a legend,” says Lehrfreund. “He was literally on his own. No one else was interested in these cases. He was a one-man band.” In 1994 Sampson went to Barbados for a conference, Penal Reform International. “He’d heard rumours that we were prepared to take cases to the Privy Council, and that I was there at the conference,” Lehrfreund remembers. “He was desperate to find me, literally sweating, just trying to find me amongst all those people. He said, ‘I’ve got hundreds of death-row cases. Will you help?’ We said, ‘Sure, let’s do it.’ That was a landmark moment.”

Over the next few years Sampson, and other Belize lawyers stirred up by him, sent case after case for appeal to the Privy Council with the DPP’s assistance. In Belize the maximum legal-aid allowance is the equivalent of £100, nothing like enough to pay for an appeal to a court the other side of the world. Thanks to the DPP, Belize’s convicts were getting the services of leading barristers, Fitzgerald and Guthrie among them, free. Over and over again, they flew to Belize.

It wasn’t easy. “We worked on a whole load of cases,” Fitzgerald says. “But they just kept on adjourning them.”

“We failed miserably,” Guthrie agrees. Those nights in the Club Amnesia came at the end of some gruelling days.

Belize lies on the route that cocaine takes north into the United States. Drugs mean money, which means violent crime. Among nations with the highest murder rate, Belize is seldom out of the top five, and there are always voices calling for more hangings. Eamon Courtenay SC, a Belize lawyer and former foreign minister, was among those who welcomed the DPP. “Most of the barristers here didn’t have any intention or expectation to challenge the legality of the death penalty,” he tells me. “The DPP said, ‘Listen, this is something you need to take up,’ but there was a cultural disinclination to do so.”

The chief justice at the time, the late Sir George Brown, was one of those disinclined. “He was pretty scary,” says Fitzgerald. “He’d say, ‘This judgment comes not from me but from God.’ There were hearings when he seemed to be saying, ‘As far as I’m concerned these prisoners can all be taken out and hanged tomorrow.’” The then governor of Belize’s only prison, Bernard Adolphus, was another who failed to see the DPP’s point of view. He kept a noose in his office. “It was a bit weird,” Saul Lehrfreund says. “He was a nice guy, really helpful. At the same time he had no problem hanging people.”

They persevered. Belize might be a small country with a harum-scarum justice system and a terrifying crime rate, but it offered the DPP another fulcrum from which the world could be moved. In most former British colonies in the Caribbean there are clauses in the constitution asserting the government’s right to execute its citizens, as the British used to do. (Lehrfreund points out the irony in these countries’ eagerness to shake off colonial rule, while conserving one of its unhappy legacies.) In Trinidad or Jamaica, the DPP team were limited to questioning the legality of a delayed execution, as they did in the Pratt and Morgan case, or of one carried out without proper notice, gradually restricting the circumstances in which the death penalty could be imposed.

In Belize, the mandatory death penalty had no constitutional protection. “So it became an important battleground,” Fitzgerald says. They couldn’t question the legality of the death penalty, but “we could argue that imposing a death sentence without an opportunity to mitigate was unconstitutional.”

So they did, over and over again. From the deck of a tourist’s boat, or through the window of the car that takes you to visit the magnificent Mayan ruins, Belize looks cheery enough. But away from the river-front with its pastel clapboard houses, away from the market stalls selling beach bags hand-embroidered in zinging colours, Belize City is a place where a dozen gangs battle for control of the drug trade, and where love stories lead all too often to crimes of passion. In Belize, the DPP found plenty of suitable cases for treatment.

ITS FIRST SIGNIFICANT success there came with the cases of Catalino O’Neill and Dean Vasquez, convicted separately of killing their common-law wives. “These weren’t sadists or serial killers,” Fitzgerald says. “These were domestic crimes. But the governor-general was a feminist who was very keen on people being executed for killing their wives. So she was refusing mercy for these guys.”

Fitzgerald and Guthrie flew out, went straight to the prison and found Vasquez in a cage on death row. “We’d literally just got off the bloody plane and there we were in this flea-infested block.” From behind the bars, as they struggled with jet-lag, broiling heat and the stench from the open sewer outside, the condemned man led them in an hour of hymn-singing, to the accompaniment of his banjo.

The date for the executions was set. Guthrie and Fitzgerald took the cases to the Privy Council, asking for leave to appeal. Their first bid failed. They tried again and, with only 48 hours to go before the scheduled hangings, the Privy Council granted leave. The two men’s sentences were eventually commuted. Two lives saved, and a precedent established which would allow an infinite number of future executions to be prevented. The lawyers were not saying that men who kill their girlfriends, whatever the provocation, should go unpunished—only that to kill the killers in their turn is neither necessary for the protection of society, nor consonant with internationally agreed principles of human-rights law. Guthrie says, “We were writing the law on provocation there.”

And so it goes on. A woman knifed her man in an alleyway, then went straight to the police to make what the prosecution said was a confession—which the Belizean barrister Godfrey Smith SC, with DPP assistance, was able to portray as a plea of mitigation—the man had been beating and bullying her for years. A man found at a murder scene, his shoes and clothes stained with blood, who somehow managed to persuade the police to give him immunity from prosecution if he told them who the “real” killers were, and who, next day, pointed out three random strangers. And Adolph, a one-eyed man whose woman threatened to leave him, and told him he was so ugly he’d never get anyone else, unless he shot another woman with whom she was fighting.

THESE AREN’T PRETTY stories. They’re the stuff of dangerous, hard-scrabble lives. But by taking them up, and applying punctilious legal reasoning to them, the DPP’s lawyers have been able to see justice done in particular cases, and to inscribe just principles in Belizean law. It is hard work, and there’s no easy reward for it. Some of the DPP’s clients are wrongly accused, and it feels good to get an innocent man or woman off, but many of them, whether brutal or pathetic, have done terrible things. The barristers, who between them give what Parvais Jabbar reckons amounts to perhaps £500,000-worth of unpaid work every year, get little thanks for helping them. James Guthrie visited a client in prison after successfully representing him before the Privy Council in London. “The governor said, ‘This is the barrister who saved your life.’ He just said, ‘Oh yeah? Well the food’s horrible in here. Is there anything you can do about that?’”

In 2002 the DPP’s hard work finally paid off. Five years earlier, one Patrick Reyes, described in court as “a man of good character with no previous record of violence”, bicycled home from work to find the couple next door had put up a fence taking in what he considered to be a bit of his backyard. He shot them both dead, then tried to kill himself. A psychiatrist who interviewed him in prison later found him to be hallucinating, and said he might have been undergoing a psychotic episode. As Belize’s new prison governor told me, “Something made him snap and he ended up killing those two, but he’s a really nice guy. Good guy, hard-working guy.”

At the Privy Council, Fitzgerald won a statement from the law lords: “To deny the offender the opportunity…to seek to persuade the court that in all the circumstances to condemn him to death would be disproportionate and inappropriate is to treat him as no human being should be treated.”

The case went back to the Belizean supreme court for re-sentencing. By this time Brown, through whom God had spoken to blood-curdling effect, had been replaced as chief justice by Abdulai Conteh, a lawyer and former minister in Sierra Leone. In his judgment on Reyes, Conteh ruled that, far from being mandatory, the death sentence should be reserved for “the worst of the worst”, applied only “where there is no possibility of reform and social reintegration of the offender”.

Reyes v the Queen was one of three Caribbean cases setting the precedent which allowed Jabbar and Lehrfreund, and the barristers, to challenge the mandatory death penalty in Uganda and render it obsolete. This began a benign version of the domino effect, fostered at every stage by the DPP, across Anglophone Africa. In 2007 the DPP assisted in a case which resulted in the high court of Malawi declaring the mandatory death penalty unconstitutional. In 2010 the Kenyan court of appeal ruled that a mandatory death penalty for murder “amounts to inhuman punishment”. As Roger Hood, emeritus professor of criminology at Oxford and consultant to the United Nations committee on the death penalty, says, “what these two guys have done is extraordinary—a great achievement.”

HOOD CAME ACROSS the DPP in the late 1990s, when he and Saul Lehrfreund were on a committee convened by Britain’s then foreign secretary, Robin Cook, to consider issues relating to the death penalty. “I formed the highest opinion of him,” Hood says. “He spoke so lucidly.” Hood invited Lehrfreund to go with him to a conference in Beijing in 2000. This winter, while Jabbar and I were in Belize, Lehrfreund and Hood were speaking together in Taiwan.

Briefing barristers to represent the condemned is only one of the DPP’s strategies. Hood is one of several academics from whom they have commissioned reports, working not just to modify the law, but also to change minds. “There are a lot of very clever people,” says Hood ruefully, “who believe the death penalty is still necessary.” His research suggests that what is needed to reduce the murder rate is not the rope, but effective policing. And then there’s the question of political will. Politicians fear that abolition would lose them elections; Hood’s surveys say otherwise. “In the first instance people say they’re in favour, but when you ask them to consider particular cases, they’re not so keen.” It’s one thing to say “hang the lot of them”, another to say “hang this desperate mother with a history of mental illness who drowned her baby”, or “hang this homeless teenager whose gang bullied him into performing a hit”, or “hang one-eyed Adolph whose woman jeered at him until he shot her enemy”.

“The death penalty brutalises the people who administer it,” James Guthrie says. Conversely, Hood reasons, its abolition alters the consciousness of a nation. From being accepted as routine, executions become shocking. “Already my daughter finds it extraordinary that people were being executed in Britain as late as 1965. The next generation just won’t believe that we did that.” Working with people like Hood, and William Schabas, professor of international law at Middlesex University, and the criminologist Dr Mai Sato, the DPP is aiming to make this cultural shift happen across the world.

Jabbar and Lehrfreund say, “We are prepared to work wherever the death penalty is imposed—we will never turn a case down.” In different jurisdictions they play different roles. If one legal instrument or international institution proves useless in a particular situation, they look for another. In countries where the Privy Council has no sway, they invoke rulings of the United Nations Human Rights Committee or the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. In Taiwan Lehrfreund was working in support of an NGO dedicated to helping the many Taiwanese with mental-health problems who are sentenced to death without ever being seen by a psychiatrist. “We produced a handbook on psychiatric practice. We’re having it translated and circulated around Taiwanese lawyers, doctors and judges. That’s another way of having an effect.”

In the Caribbean they organised a seminar for 70 local practitioners, led by Professor Nigel Eastman, one the Britain’s foremost forensic psychiatrists, who has given his services to the DPP unpaid from day one. In China they held workshops attended by judges from the Supreme People’s Court in Beijing. In Japan they published a report and met people from the ministry of justice, starting a conversation that may take years to yield results. They are used to taking it slow.

THE PARTY THAT flew to Belize illustrates their approach. Parvais Jabbar was there to present the report the DPP had commissioned from a barrister, Joseph Middleton. Middleton was also there, interviewing a client, and so was James Guthrie, greeted by Belizean lawyers as a visiting celebrity. Richard Latham, a forensic psychiatrist working for the DPP pro bono, was in the prison day after day, interviewing prisoners on murder charges to assess whether they were of sound mind. Belize has no psychiatric hospitals, and only one psychiatrist. Latham came back to the hotel each evening wrung out. I ask him why he does it. Back in Britain he works in an NHS medium-secure unit. He also takes on up to 15 legal-aid cases a year, working evenings and weekends. Enough, surely, to use up his energies? No, he says. He’s been in Kenya on behalf of the DPP, training lawyers and psychiatrists to work together. He has testified as an expert witness in a murder case in Trinidad. “It’s not just that I’m giving my time free,” he says. “I’m getting something out of it too. This is incredibly interesting.”

In the Belize prison, when John Woods took over as governor, there were inmates living on the roof, the only place where they felt safe. On his first visit, in the 1990s, Guthrie interviewed a client through the bars of a cell in which men were crammed so tight that only one at a time could lie down to sleep—on the floor. “It was horrible, really horrible.”

“That was usually for protection,” Woods says. “The black guys from Belize City had the Spanish boys pretty well intimidated. You’d get 12 Spanish guys staying in one cell because they felt safer that way.”

Things aren’t quite so bad now. The last killing in the prison was four years ago, the murder weapon a toothbrush, sharpened to a lethal point by grinding on the cement floor. But Woods still has to be careful. “You can’t put someone in the same cell as somebody who’s killed his brother.”

Our tour is far from complete. There are over a thousand inmates here, but few people to be seen about. “We have to keep the remand prisoners in their cells 23 hours a day,” Woods says. “Some are fresh off the streets. They’re more aware of the gang wars going on out there. The remand block is pretty hostile.” One of Middleton’s recommendations focuses on the delays that keep prisoners there, awaiting trial: one man has been on remand for seven years.

Jabbar and Middleton have a meeting with a Rastafarian who is now the only occupant of death row. While they talk, Guthrie and I visit the women’s block. The main room is pretty, its walls distempered in pink and turquoise, the inmates, mostly very young, wearing their own bright clothes. But their stories are not pretty at all. Among those turned out of the cells to meet us is Lavern Longsworth, a slight, nervous-looking woman who killed her man by throwing kerosene over him and setting it alight with a candle. A former attorney-general, Godfrey Smith SC, represented her in the court of appeal. The DPP sent out a British barrister and a forensic psychiatrist. Between them they persuaded the court to commute the charge to manslaughter, on the grounds that White had been abusing Longsworth for years. On the night in question, he’d bullied her into giving him money for cocaine. Another precedent set. Battered-woman syndrome is now recognised as a defence in murder cases in Belize.

BACK IN THE rehabilitation unit, the national anthem over, three young men stand up in turn to tell us their stories. A 24-year-old who has been fending for himself since he was eight reports that imprisonment has reunited him with his mother. She came to visit him. Once. A year ago.

Woods asks us to address the prisoners. “Just give them some encouragement,” he whispers. I get to my feet and stumble through something. Guthrie, who has been at the back taking photographs, comes forward and graciously compliments the inmates on their self-discipline. Then Parvais Jabbar stands up. “Keep trying. Keep striving,” he says. “Lead the best lives you can. You might get out, then find yourself back here. That doesn’t mean you’ve failed. You just have to keep trying.”

This could be the mantra of the Death Penalty Project. Even in the toughest parts of Belize, a decent life can be lived. Catalino O’Neill, sentenced to death for killing his girlfriend in 1991, reprieved after Fitzgerald argued his case twice over at the Privy Council, is now a law-abiding bus-driver. Lenton Polonio, convicted of murder in 2004, cleared by the Privy Council, is washing cars. Twenty years ago it seemed almost as hard for a couple of lawyers to kill off the death penalty around the world.

It’s not done yet, but the mandatory element has gone in 13 countries. Hundreds of death sentences commuted or quashed. A dialogue begun with the Chinese. Inroads made in Taiwan and Japan. Jabbar and Lehrfreund are on the way to their stated aim: putting themselves out of a job.

Lucy Hughes-Hallett is a cultural historian. “The Pike”, her book on Gabriele d’Annunzio, won the 2013 Costa biography award and the Samuel Johnson prize.

Photographs from the prison James Guthrie